Case Study 1: Boise Refugee Community Garden Project

Introduction

Upon embarking on this study of refugee garden programs, I stumbled across the Boise project via the great search engine. Admittedly, I have never been to Boise, Idaho, but nonetheless, I was quite surprised to find that there was a refugee community there. My surprise was due to my ignorance as I soon found out from speaking with Patty Haller, the assistant director of the Idaho Office for Refugees. Haller and I talked on the telephone for over an hour about the garden project that she initiated and still directs. We also discussed recent resettlement trends—soft landing spots, federal programs, and the recent demographic shifts in the refugee population. I am deeply thankful for her patience and willingness to share her knowledge.

There is a wealth of on-line information that can offer details on this project. Here I summarize the project and report findings gleaned from my interview with Patty Haller.

|

Image source: Idaho Center for Refugees. Link to original article here. |

Project Overview

Started in 2004, three Boise refugee community gardens now support 50 multi-generational families from Afghanistan, Somalia, Liberia, Ukraine, Bosnia, and Sudan.

Most of the refugees sent to Boise are “free cases” without existing family networks elsewhere in the U.S. Gardeners in the program all had basic gardening skills prior to their arrival in the U.S. As is typical in most community gardens, there is a waiting list to receive a plot.

The program was designed by to serve the elderly refugee population. Elders from foreign countries have an especially difficult time adjusting to life in the U.S. due to their social isolation. Since they usually do not seek employment and often end up acting as babysitters for grandchildren, the elderly are less likely to learn English and less likely to venture out of the home. The Office of Refugee Resettlement provided a start-up grant for the garden which was justified as a means to gently push refugee elders down the path toward citizenship.

Patty Haller, the assistant director of the Idaho Office for Refugees, wrote the grant application and collaborated with the Agency for New Americans, English Language Center, and World Relief to create three gardens. A large volunteer network, faith-based, private, civic, Americorps, and otherwise assisted in the construction and continues to help with maintenance.

Project |

Initiated By |

Serves |

Primary Goal |

Delivered Benefits

|

Boise Refugee Community Gardens |

Refugee Agency |

Elder Refugees and Families |

Reduce Isolation |

Fresh Food

|

The Faith-based Community and Soft Landing Spots

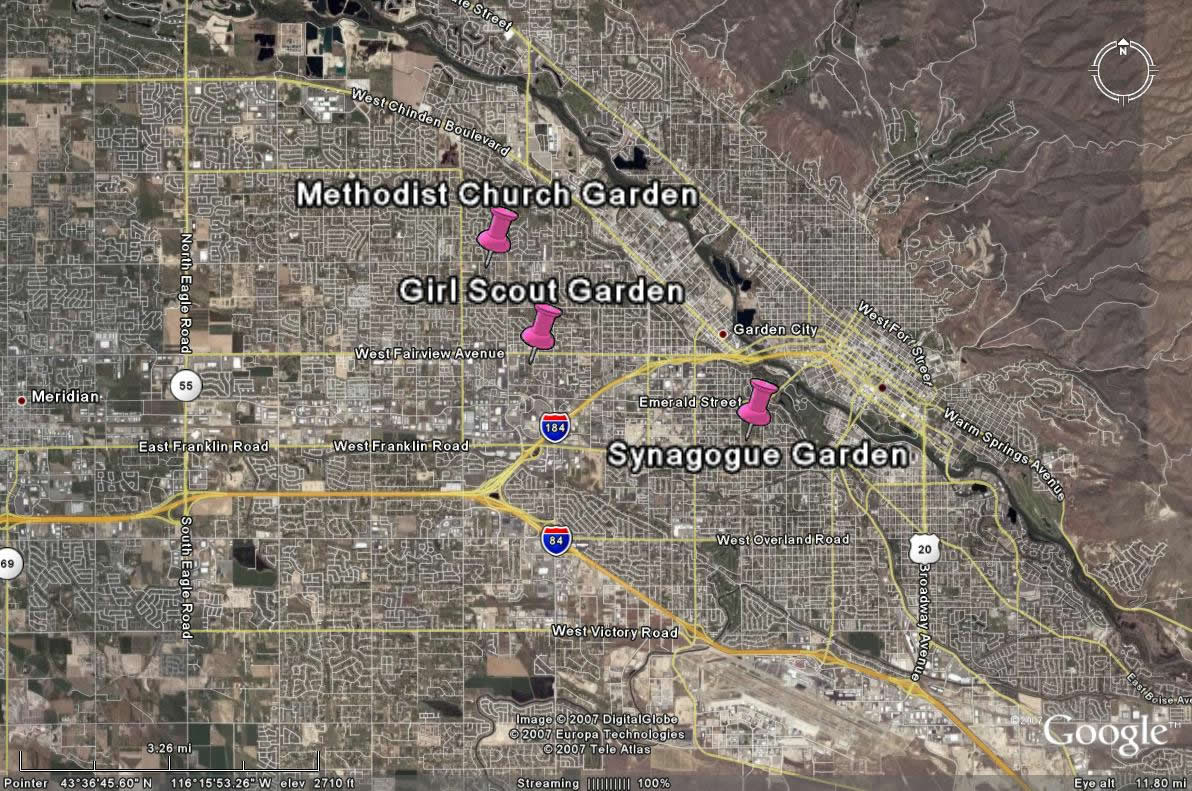

All three gardens are on land donated by religious groups and all lie within city limits. The pioneering plot lies on the land adjacent to the Ahaveth Beth Israel Synagogue which is just half a block down the street from a multi-family complex where many Somali Bantu families live. This convenient location allows gardeners to walk to the site. The congregation is not only supportive but proud of the gardens. In fact, the congregation has been nationally and internationally recognized for its civic function.

“The garden has been a tool for teaching. The children participated in a Jewish nature camp… The teens built raised beds for senior and handicapped gardeners. Synagogue members joined community work days to help refugees till. Even into the winter, we have begun a tutoring program.”

–Sherill Livingston, synagogue member <1>

The second garden is behind the headquarters for the Girls Scouts of Silver Sage. It is also managed by the synagogue through an Americorps and volunteer program. The third garden is on site with the Hillview United Methodist Church and was initiated independently by an Eagle Scout.

In our interview, Patty Haller underscored that the willingness of Boise’s residents to support the gardens is a testament to the theory behind soft landing spots. Here, and in other similarly-situated small cities, “people, especially churches, want to become personally involved with refugee programs.”<2> The gardens could never have happened without the land grant and volunteers from the church and synagogue.

|

Map of Boise from google maps |

Greater Community Benefits

However, the faith-based community was not alone in their generosity; grants, technical assistance, infrastructure, tools, plants, soil amendments, and volunteer hours also came from other private and public sources. A true community-wide effort, Haller declares that gardens can be something for an entire community to rally around, as they are highly visible, attractive, part of the local food movement, and seen as a testimony to work ethics.

“The refugee garden project has helped to promote mutual understanding among refugees and between refugees and the broader community. People now view refugees as multi-dimensional individuals who have needs but who also make an important contribution to the quality of life in our community.”

—Patty Haller, Project Director <3>

Intra-community and Personal Benefits

Though the gardens are highly celebrated by the refugee service sector, the professional sociologists, and local residents, the most important benefits are those felt by the gardeners themselves. In fact the simple re-association of from “refugee” to “gardener” has transformed the way Somali Bantu viewed themselves. English Language Center director, Steve Rainey, reports that prior to the garden program, Bantu were not proud of their agricultural heritage. (Most Bantu were subsistence farmers before arriving in the states.) Now, they take pride in the skills that they have brought over from their homeland.<4>

Rainey also noted that the act of planting, watering, weeding, and harvesting, helps refugees deal with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), which is defined by mental health professionals as a foreshortened sense of the future.<5> Those suffering PTSD are unable to set goals or move toward them. Gardens reintroduce sufferers to the concepts of time, investment, and reward, which helps motivate them to become participatory actors in society.

In addition, the gardens provide a space for idea exchange and fun. They are important venues for sharing food, gardening advice, and stories about life before Boise. Aliya Ghafar-Kahn from Afghanistan says that “the time in the garden is as important as the vegetables.”<6>

“I went to grow my food; instead I grew a friend”

—Saliha, gardener from Afghanistan<7>

Service providers and educators have observed marked changes in participants. The garden served as a non-threatening and informal site for learning English. The multitude of languages spoken on site forced gardeners to use English as a common means of communication. Armed with more confidence and better language skills, gardeners became less afraid of the bus system and started attending more events and activities.<8> In short, they assimilated.

Outlook for the future

Following recent newswires, it looks like Boise has indeed proven itself to be a successful soft-landing spot for resettled refugees, despite being 91% Caucasian. The Assistant Secretary with the Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration, visited Boise in October, stopping to make an official speech at one of the community gardens. She announced that Boise will be one of the destinations that will be receiving some part of the 12,000 Iraqis that will enter the U.S. as refugees next year. To date, Boise has settled approximately 3,000 refugees since the 1980s—around 700 during this past year.<9>

|

Assistant Secretary Sauerbrey at the Community Gardens Image source: Dept of State website |

As far as the gardens go, Patty Haller said that the ORR grants have shifted toward Economic Development initiatives, including one “Rural Initiative” that promotes starting or expanding refugee agricultural enterprises. Haller says that she will in turn shift her own programming toward this end. She is working on developing a model market garden program, which will bring a host of new challenges. The primary goals of agricultural development projects are completely different than those of the community gardens. The gardens were developed to reach as many people as possible and to promote social interaction. A market component will completely change the dynamic. The risks will be higher, so the project will need tighter control mechanisms.

=====

<1> Daranee Petsod, ed, “Growing Community Roots: The Boise Refugee Community Garden Project,” Investing in Our Communities: Strategies for Immigrant Integration (Sebastol ,CA: Grantmakers Concerned with Immigrants and Refugees, 2006), 183 http://www.gcir.org/resources/gcir_publications/toolkit/169-186_social_cultural.pdf (accessed December 5, 2007)

<2> Ibid.

<3> Haller, interview by author, Cambridge, MA, November 14, 2007

<4>Steve Rainey quoted by Patty Haller, “Growing Community Roots: The Boise Refugee Community Garden Project,” The Art of Community: Creativity at the Crossroads of Immigrant Cultures and Social Services (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Institute for Cultural Partnerships and Grantmakers Concerned with Immigrants and Refugees, 2006), 19 http://www.gcir.org/resources/gcir_publications/ArtFinal.pdf (accessed October 20, 2007)

<5> Ibid, 19

<6> Haller, “Growing Community Roots: The Boise Refugee Community Garden Project,” 20

<7> Ibid, 18

<8> Petsod, 183

<9> Haller, interview by author, Cambridge, MA, November 14, 2007